Escape from Madness

Spouting Curses, Waving Signs

‘Something in me died’

by Thomas Adcock

Copyright © 2023 – Thomas Adcock

NEW YORK CITY, near America

October 7 leaves us with yet another milepost along the highway of human depravity. Yet another foul deposit for the cesspool of tribalism; yet more billions enroute to the munitions industry coffers; yet more crime without consequence; yet more thunderous certitude sung by the usual chorus of fools and fomenters with opposing claims to The Truth, the Whole Truth, and nothing but The Truth.

Yet more suffering among the young, and the sadder but wiser old.

Yet more blurring of fact and fable.

Yet more resistance to nuance.

Yet more blood.

Yet more blood.

Always, more blood.

•

On the morning of October 7, the ruling Hamas authority in Gaza—an impoverished, politically crippled Palestinian territory roughly double the size of the skinny island of Manhattan—launched a blitzkrieg of butchery in neighboring Israel. In the cause of grievance, some two hundred and fifty Jewish lives were taken in the opening hours of an intricately planned terrorist operation; nearly two thousand more Jews were maimed and hundreds abducted—as hostages in yet another holy war.

Soldiers of the Hamas military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, bulldozed through towering walls that ring Gaza, then poured into the Israeli frontier, guns blazing. Paragliders transported allied units to twenty-two civilian communities of Jewish settlers that parallel the walled enclave of Gaza.

High on psychoactive capsules of Captagon—widely used by British, American, and Nazi troops during World War 2 as inducements for barbarous conduct—a first wave of Hamas gunmen swarmed the desert site of a music festival. There, they slaughtered dozens of young Jews dancing in the sand, joyfully exhausted from a dusk-to-dawn “rave” that was part of the festival. Drug-fueled soldiers photographed themselves near a cluster of portable toilets at one end of the festival grounds, where they used North Korean-made AK-47 machine guns to spray bullets through the privacy doors.

At other points, Hamas commandos used grenades to kill ever more civilians as they rampaged through Israeli villages. They crashed into homes of the kibbutzim and shot down men who dared to move; they seized hundreds of women and children as hostages to holy war, imprisoning them in the dank maze of underground tunnels and hideaways once returned to Gaza. The Reuters news service of Britain, not given to exaggeration, reported incidents of Hamas soldiers raping women, hacking off arms and hands of civilians, and beheading at least one child.

Stunned by the efficient ferocity of attack, the vaunted Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) were flummoxed. An over-reliance on technological warning systems had rendered them flat-footed against low-tech methods used to the advantage of Hamas. Rather than cellular communication in voice and text, Hamas coördinated its attack in a pre-computer, un-detectable, un-hackable manner: Notes on paper slips that were burned after reading, landline phones were used for calls, underground meetings were genuinely face-to-face rather than zoomed.

Israel’s generals had badly underestimated the combat capability of Hamas, whose backfield fighters sent barrages of rocket fire to brace the brutality of foot soldiers on the ground. The generals were absolutely gobsmacked when Hamas landed missiles in four Israeli cities—including the Tel Aviv-Jaffa metropolis, with its population of more than four million.

During the initial five (!) hours of Hamas terrorism, the Middle East’s mightiest military machine was made still. Israel was stymied by a well-mapped raid. But when the IDF was at last roused, retaliation was swift. Early-on, a near equal number of dead and maimed Hamas soldiers fell away. Unrelenting Israeli airstrikes made rubble of commercial and residential buildings in densely populated, Israeli-controlled Gaza strip aside the Mediterranean Sea.

Home to some 2.3 million Palestinians, most under the age of 18, Gaza lives with blockades variously imposed by Israel since the Six-Day War of 1967. In area, the Gaza strip is modestly larger than the teeming island of Manhattan at the heart of my own city.

As I write in these final days of October, humanitarian aid organizations based in the West estimate a civilian death toll in Gaza of seven thousand, a number that may soon be dwarfed by more killing. Almost half the families in Gaza have been displaced from their homes, yet forcibly kept in place—in the streets, among falling buildings and falling bombs.

Food, water, fuel, and medicine is rationed or vanished in Gaza—necessities for ordinary citizens. The Hamas élite, secure in bunkers and tunnels beneath the streets and reviled by many of the hoi polloi, want for little.

The territory is sealed against entries and departures. Physically, there is nowhere in Gaza for ordinary citizens to escape the madness. That Qassam troops managed to bash through barrier walls that isolate Gazans from Israel and the rest of the world is a wonder that remains unanswered.

Troll farms of disinformation around the globe sprang into action to exploit the void of legitimate news exchange. Social media is now crowded with postings of racist xenophobia—each communiqué an effort to organize competitive rage, to infect public order with cult-worthy propaganda, to prompt a fresh flow of cash to amoral profiteers of hate.

Likewise, campus passionistas in the United States and elsewhere are quick to choose “sides” in the internecine conflict between Hamas and Israel. In shallow anger, students march daily through ivied quads of academic privilege, spouting curses and waving protest signs. (Better they might spend time and energy in critical thought about the history of the so-called Holy Land, and how it has been recorded through the centuries by imperfect rapporteurs.)

Naturally, the politicians have weighed in.

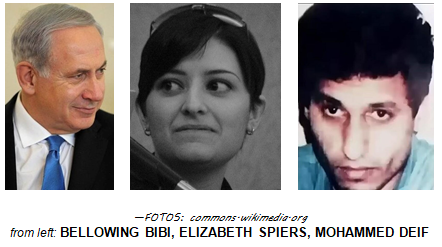

Mohammed Deif, shadowy mastermind of the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades and a man with a single functioning eye who never appears in public, said in a written statement to news media that the October 7 attack on Israel was “only the start” of “Operation Al-Aqsa Storm.” He called on brother terrorists in neighboring Arab countries to join the Hamas cause, a crusade that calls for the destruction of the Israeli state and the concomitant death of its people.

And from Jerusalem came the vows of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu: elimination of the Hamas political structure, and extermination of Qassam militants. Known among brass hats at the Pentagon in Washington as “Bellowing Bibi,” Mr. Netanyahu declared on the second day of the attack, “Every member of Hamas is a dead man walking.”

Leaders of Mr. Netanyahu’s extreme rightwing governing coalition were delighted with his fiery rhetoric. Jews everywhere went on alert, their old fears risen to the surface; fears bred in the bone by generations of family members fallen victim to pogroms. Here in New York, with a population of Jews second only to that of Israel, the phrase “Never Again” is heard every day. Here in New York, many who go to mosque every day shudder as they pray.

Invective and ignorance and fearful talk being the soundtrack of wars down through the ages, the roots of today’s bedlam are familiar to perceptive journalists of the modern day. Serious, independent journalists such as Elizabeth Spiers, who writes of the zeitgeist:

“The impulse toward loud, reductive declarations reflect genuine fear about horrors that lie beyond words. Simple binaries imply simple solutions. And it’s much more pleasant to tell yourself that you stand on the side of good, against evil, than to question whether the lines of demarcation were drawn correctly.

“Sitting with uncertainty is hard, especially when social media have primed us to expect perfect real-time information during traumatic events, and to want instantaneous answers and resolutions. Moral certainty is an anchor we cling to when factual certainty is not possible. And the faster we express it, the more certain we appear. The most righteous among us post, and do so immediately.”

•

Muslims and Jews both own valid—and ancient—claims to the lands of Palestine and Israel, as we know the war-stained region today.

In a recent sermon at Congregation Beth Elohim in Brooklyn, New York, Rabbi Rachel Timoner laid out the facts of a divided life: “Here we are, two peoples, stuck together. Both peoples deserve safety, freedom, self-determination, and peace. There is no way [forward] without recognition of that reality.”

The rabbi added, “Any agenda that promotes a future or present where one people rules over the other is inhumane and immoral. Any agenda that promotes a future for just one people on the land, either Palestinian or Israeli, is inhumane and immoral.”

So very reasonable, that message. But in the fog of Middle East antagonisms, reason alone doesn’t stand a chance. Something of greater strength is necessary to bolster reason. Where is Solomon when we need his wisdom? (Oy vey!, we might say. Or the Arabic equivalent, Awy fiy!) By his lights, the late King Solomon (970-931 BCE) would likely define the enemy of Jews and Muslims alike as war itself.

My friend S.J. Rozan, the New York architect and crime novelist, would seem to agree. For her latest Substack entry, Ms. Rozan wrote:

“[People] are not hardwired to kill. You have to be inflamed to do that, to be convinced that those people you hate are so terrible they deserve for you to kill them. It’s damn hard to inflame people against soldiers only. War is for the purpose of wiping out the enemy. Including the enemy’s giggling toddlers…

“Am I saying then that we might as well accept the slaughter of civilians because that’s how war is fought? God, no, I’m saying we need to accept that that’s how war is fought and stop the slaughter of civilians by stopping our default resort to war.”

•

The deadly Saturday morning of October 7 ushered in the first full day of a Jewish sabbath—Shabbat. In the fraught Palestinian territory of Gaza, bordered on the east and north by Israel and Egypt on the south, a one-year-old Muslim girl named Sara took her first steps in the family apartment. Her four-year-old brother Ali watched.

And watching by live video was the children’s father, Khalid El-Astal, nearly a thousand miles away in Riyadh. There, in the Saudi Arabian capital, he was completing a year’s work at a graphic arts company, a job he was grateful to have after two failed business ventures back home in Gaza. His wife, Ashwak, operated the cellphone camera that allowed something as close to family gathering as they would have for a scary stretch of time—weeks or months or years; they could not know.

Nor could Khalid and Ashwak know that in a matter of hours they would be living moment by moment in a frightening purgatory of war.

In an interview via WhatsApp, Khalid told me of his personal agony in being separated from his young family. By dint of his birth, thirty years ago in Ireland when his own father was pursuing a doctorate degree in physics at a university there, Khalid holds dual Irish-Palestinian citizenship. Such is a blessing that extends to little Sara and Ali, but not to Ashwak, a native Gazan.

“They can lift my children out, but not my wife,” said Khalid, who does what he can in navigating through diplomatic bureaucracy at the Irish Embassy in Riyadh. “They’re working on it. It’s something I cannot do myself.”

Meanwhile, Khalid sits and waits in the small room he rents in Riyadh, where he sleeps fitfully when not working a job that does not match his educational status; he holds a master’s degree in physics. The cheap room allows him to forward most of his salary to Ashwak, trained in civil engineering management.

In the first days of war, Khalid did not sleep, frantic as he was with thoughts of his wife and children. Of their struggle in fleeing Gaza City in the north for the dubious safety of southern Gaza.

“I was dying, something in me died,” said Khalid, who has known five wars over the past fifteen years in the Palestinian territories. This time, he said, “It’s something different. Every ten minutes or so, some family is dead. Now there is no food. Everybody is just waiting to die.”

The family of Khalid’s closest friend died in Gaza when trapped in a car hit in a bombing raid.

“He was like a brother for me,” said Khalid of his friend. “His wife and children lost their lives. He lost an arm.”

Khalid worries that his friend might kill himself.

“After this war, Gaza will be a place where no one can live,” said Khalid. “My dream is to be reunited with my family in Dublin. But we really don’t know what will happen next.

Khalid El-Astal, a devout Muslim, does know what might quell violence in the Middle East: “Religion is for people, not for nations.”

—NOTE: At deadline, word came that Ashwak and the children were injured when the house where they were staying in the south of Gaza was bombed. Ashwak was hospitalized for severe burns to her face. She was unable to move. The children are in hospital care, but improving. Further: Khalid was forced to leave Saudi Arabia for Türkiye. He hoped to make his way to Dublin. Khalid and his family, he said, are “tired from life and war.”

On the morning of November 1, Ashwak died in hospital.

•

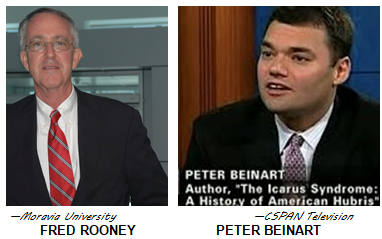

Assisting the El-Astal family through the legal maze they face to reach their dream of a new life far from military conflict is Fred Rooney, a globe-trotting American attorney attached to the United Nations Development Program.

Mr. Rooney met Ashwak in Gaza City, weeks prior to the Hamas attack on Israel. Under the U.N. aegis, he participated a Gazan university program that serves professional women such as Ashwak. Because it is a matter dear to his heart, Mr. Rooney urged Ashwak to begin the years-long process of filing for Irish citizenship on the basis of marriage.

What with the ongoing war, Mr. Rooney hopes to broker an exception to timing protocols that currently prevent Ashwak from leaving Gaza, by way of the Egyptian capital in Cairo, for Dublin with her children.

Mr. Rooney has worried about the dangerous U.S. political climate created by the 2016 election of Donald Trump as president, a danger that spills beyond American borders. Accordingly, he tells anyone who will listen that those who qualify for second and even third citizenships should apply—at once.

“There are a ton of Americans who do qualify,” he said. “It’s good to have that extra passport.”

Sometimes, he added, there comes a critical need for escaping one’s first country. Case in point: Ashwak El-Astal.

•

Peter Beinart, professor of journalism and political science at the City University of New York and editor at-large at Jewish Currents magazine, offers a vital element to the mix of serious-minded analysis of a complicated war story:

“The denial of Palestinian freedom sits at the heart of this conflict,” he wrote in a recent essay for the New York Times.

Resolution will require Palestinians to “forcefully oppose attacks on Jewish civilians, and Jews to support Palestinians when they resist oppression in humane ways—even though Palestinians and Jews who take such steps will risk making themselves pariahs among their own people.”

Further said Mr. Beinart of a path to lasting peace, “It will require new forms of political community, in Israel-Palestine and around the world, built around a democratic vision powerful enough to transcend tribal divides.

“The effort may fail. It has failed before. The alternative is to descend, flags waving, into Hell.”